Value. What's in a Name?

Experts share recommendations on accessing value through supplier partnerships.

Let’s start at the beginning. Actually, back to the very beginning, or close to it at least. Consider the Greek word αξία (“axia”). It was translated to mean a variety of things, namely: worth, merit, valuation, denomination, and worthiness. Yet, thousands of years later, here we sit, debating the true meaning of its root word value. Yes, that tricky homonym that escapes a clear consensus across the health care landscape, invoking the use of equations depicting outcomes over cost, while at the same time confusing the less astute with contrasting terms such as affordability. Promises of value in healthcare abound and truly, the seas of change have moved the paradigm from volume to value-based reimbursement.1

Over time, suppliers have promised healthcare organizations (HCO) ever-increasing assurances of value as it relates to clinical outcomes and the associated costs of a single product or service. In fact, if you added up all the perceived value discussed by suppliers ad nauseum, it would be difficult to understand why the HCO has not achieved a negative spend each year! So, where do the discrepancies lie? Are the clinical outcomes tangible and measurable? Is it the promise of decreasing relative risk or absolute risk? Should cost be defined as unit cost, total cost of care, cost of ownership, cost over the continuum, or cost avoidance? More importantly, what is the long-term financial result that these goods and services will have, e.g. our ability to reduce readmissions, prevent infections, improve patient satisfaction, etc.?

Today, value-analysis professionals and others responsible for a facility’s bottom line are actively seeking to blaze new paths forward, away from the traditional transactional relationships of the past, toward the concept of value-based-partnerships (VBP) and value-based-contracting. In January 2021, an advisory board was assembled consisting of several value analysis leaders to help advance how suppliers and HCOs can accomplish meaningful partnerships. The meeting was kept

To set the stage for such an important discussion, the board was asked to begin the meeting by presenting an exemplar of when supplier partnerships brought the most value to their respective organizations. The board agreed that an important first step was for the supplier to come to the table prepared. This seems like common knowledge, however, the board members agreed that all too often suppliers ignore a very impactful step when introducing a new product for potential acquisition. JR indicated that the supplier can save the HCO save time by being prepared with the basics - things like:

- Published clinical based evidence

- Outcomes

- FDA clearance

- SKU numbers, sizes & shapes

- Catalogue Numbers

- Packaging sizes, with units of measure

- Pricing

- Reference accounts

- Electronic basic promotional materials

So, be prepared. Present a value-analysis-package and start the discussion off on the right foot. Another important collaboration action was equally simple, yet effective: LISTEN!

Suppliers who first tried to understand the needs of the HCO and then demonstrated adaptability and creativity in customizing solutions always standout.

More often than not, suppliers tried to force their solution and structure on an organization. However, HCOs have different challenges, ways of operating, and pain points, making flexibility a definitive skill. After all, a partnership indicates the supplier - HCO will work together to achieve the right approach, not a one-sided affair. Listening also leads to communicating. The best exemplars involved very transparent and clear communication. This involved both supplier-distributor-HCO communication as well as ensuring supplier communications with internal stakeholders, such as surgeons, were open and forthright. Additionally, implementation efforts by the supplier in terms of educating staff and key opinion leaders often determine success versus disaster when a new product is brought into the system.

Tying these concepts together was a commentary by BS. She shared an experience at her facility which struggled with access to clean, available electrocardiogram (ECG) cables, impacting both access to care and the risk of surgical site infection, especially in cardiac surgery patients. The HCO reached out to ECG cable suppliers to determine the potential of disposable cables and a possible reprocessing program. The supplier that was ultimately selected approached the problem by first listening to the needs of the facility and responded with a variety of options that could potentially meet the need of the HCO. The resulting partnership was a customized program that both met the needs of the hospital, while also providing the supplier with an improved offering it could potentially also offer to other customers. The partnership agreed on all aspects of training, conversion, and hands-on trouble shooting. The ability of the supplier to deliver throughout the process and participate in ongoing tracking of key performance indicators led to this supplier being a longterm preferred supplier. The result was improved quality (cables and clean electrodes available when needed, mitigating risk of SSI) and overall value. The value stemmed from comparing the HCO’s initial state (buying new reusable cables), versus the new process (on-demand disposable cables) - the move to the new process considered cost as well as other considerations. The key to success was the supplier’s hands-on approach and willingnes to meet with internal subject matter experts to ensure their

The second portion of the advisory board presentation focused on the question, what does a good value-based partnership mean to you and how do you measure value? While a partnership suggests an association between two or more persons, relationship suggests that the two are connected. For this reason, the committee’s view on achieving a true value-based partnership was to go one step further and ensure that the HCO and supplier were truly united to address, solve and monitor the impact of the product on hospital identified challenges to achieve sustainable results.

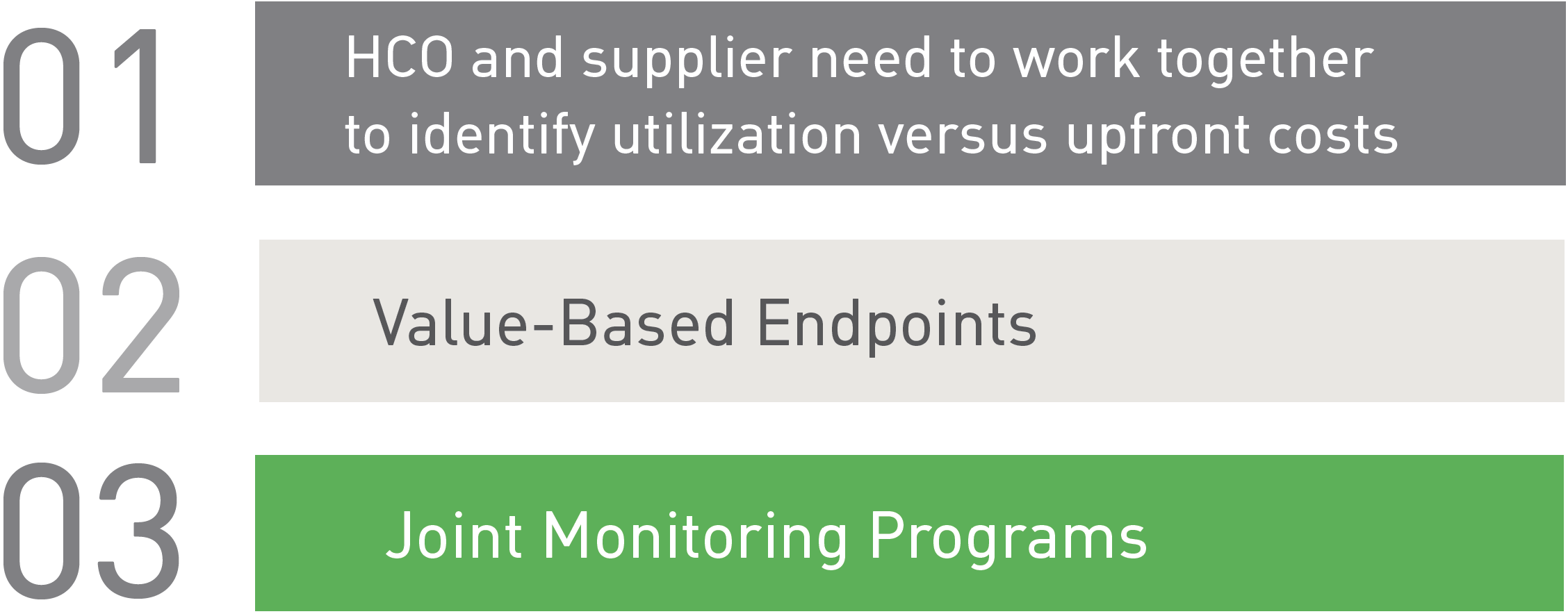

3 Principle Themes

Emerged From This Discussion:

When it comes to managing cost, utilization is key to determining return on investment (ROI). JR commented, “there’s only so far a supplier can drop their price, so, it’s not how much we pay for what we use, it’s how much we use what we pay for.” This statement reinforced the need to differentiate upfront costs from actual performance of a product, especially when comparing commodities. More importantly, the parties need to agree on exactly how each “value-component” will be measured. This should be based on the supplier’s customized value proposition and the HCO’s primary goals. One example to underscore this point from the board was an experience where a hospital converted to a product approximately 50% cheaper than the original product being used, with an appearance of hospital savings.

However, in review of the monthly utilization figures after the conversion, the value-analysis team revealed that the usage had tripled, which was not reflective of an increase in patient numbers, nor did it result in differences in clinical outcomes. Consequently, the cheaper product was costing the hospital more through a negative return on investment – the complete opposite of what they’d intended. Therefore, the board agreed that long term gains through improved outcomes and product performance – truly the total value they aim to capture – should be assured through joint monitoring and education on proper product usage with the supplier to avoid the allure of a ‘quick-savings”.

Specifically , suppliers who flag the potential of overutilization issues ahead of time and suggest corrections that will control utilization costs, even at the expense of short-term supplier sales decreases, will encourage trust and secure long-term sales commitments.

“The best suppliers are the ones who recognize problems but also want to help fix them, providing consistency and sustainability, with both short-term and long-term solutions.” Value in the minds of the advisory board is born from this statement. Moving forward, the supplier- HCO relationship needs to focus on outcomes that reduce variation and directly impact the health of the population, and resource allocation for the hospital. For example, how can the VBP address readmission rates, reduce amputations, and achieve sustainable reductions in hospital acquired conditions such as pressure injuries and hospital acquired infections? Risk-sharing relationships have been suggested to approach these topics, however the board indicated this is not possible for every situation as agreeing on a single point of data that is not overly influenced by staff variation is hard to find. Instead, the supplier should listen to the challenges and needs of the HCO and consider creative opportunities to meet the need, not offering a take-it-or-leave-it-cookie-cutter corporate approach. HCO leadership has become savvier in their understanding of clinical outcomes and the value-analysis-nursing-leadership collaboration is crucial for success.3 There is a willingness to spend more or invest in a product, especially when it can be tied to outcomes that matter: shorter length of stay, decreasing time to healing, reducing procedural times, et al – it’s the total value that really matters. When a relationship goal can be established, the HCO is often willing to engage in a paid conversion-and-evaluation period where a reasonable amount of time to accomplish the goal is decided ahead of time, the impact is monitored, and the supplier partnership involves a commitment to successful implementation, utilization, and outcome monitoring.

However, measuring quality and value can be difficult. Differences in infrastructure, clinical processes, and short-term versus actual outcomes have led some to suggest that VBP programs need to be designed by stratifying measures based on their impact on cost effectiveness and true clinical benefit.2 Avoiding soft dollars is key. For example, estimations of reduced nursing time don’t result in actual savings for the hospital if they are still being paid for their full shift. So, these soft-dollars must be translated into actual value, such as increasing case turnover in the operating room or increasing number of visits in the clinic. Too often, the board agreed, suppliers may follow a sale with a hands-off approach that will typically comes back to bite them. Given the distraction caused by COVID-19 on value analysis professionals, the supplier should proactively provide updates on integration success and outcomes, anticipating the HCO need, and reducing costs when possible, instead of being reactionary.

Demonstrate the ability of a suite of products to solve a problem by decreasing the variability in practice.

The final portion of the advisory board meeting centered around the concept of evidence. What evidence do HCO value analysis and clinical representatives need to help inform their decision-making process? Engleman and colleagues described the value-analysis committee’s consideration of differential within a particular product area as easy math when it comes to commodity products. In their opinion, when two or more suppliers exist for products with similar indications and features the decision is only price.4 However, this line of thinking can ignore evidence of true performance and outcome differences, leading to the use of a dangerous phrase, ‘clinically-acceptable’. If value is truly clinical outcomes divided by cost, then clinically-acceptable should not exist. This led board member RG to indicate that supplier studies may ‘get you in the door’, but often we want to do our own hands-on study for true comparison. For example, she noted that while foam dressings may be considered the same in wound care, they perform differently and therefore an evaluation of how the products truly change clinical outcomes and impact utilization is often needed on the ground level. Often, HCOs look for independent, non-industry driven research to aid in their decision-making process, but highly controlled studies such as randomized controlled trials do not provide pragmatic information as to how the product will actually perform across the wider organization. To supplement product efficacy research, the board stressed the benefit of internal and external content experts to help drive the discussions and decision-making process for clinical representatives and value analysis professionals. Getting a deeper understanding of the research, the performance attributes, and the experience of other facilities helps HCOs to know what ‘real-life’ will look like if a particular product is brought into the facility.

A potentially novel approach for suppliers contradicts the one-product-one-outcome based traditional research. For example, looking at the addition of a single product that has a direct or indirect potential benefit on reducing a hospital acquired condition ignores the lack of impact to house-wide rates when variation in risk exists. To combat this issue JR suggests that bundled product or kit-research may be the better answer. For example, if a supplier has a kit of products that all work together to prevent a HAC, then consider that the HCO may be open to the idea of an internal trial on the introduction of a comprehensive-solution to more completely address the issue. In other words: demonstrate the ability of a suite of products to solve a problem by decreasing the variability in practice.

Moreover, the board indicated there are several missing endpoints in current product focused research. In the future, suppliers should consider what total cost of ownership looks like for the HCOs they serve and focus on research that examines variables relevant to the settings which add to that total cost. Additionally, patient reported outcomes measures (PROM) are of increasing value. Even if a product cannot differentiate itself from competition based on a specific clinical outcome, if the product improves the patient experience, satisfaction, or ease of access, the product may be considered of higher value to the HCO. While patient satisfaction scores are dependent on an entire host of variables, patients that feel valued are more likely to follow through in the recommended treatment plans, return to a provider for ongoing care, and may be less inclined to direct complaints at a physician or facility when their needs have been addressed.

In addition to clinical studies, therefore, the board recommends that this be accompanied by data from similar size/setting facilities who have experienced the results that are being offered by the supplier. Most importantly, suppliers who can drive compliance and sustainability have a considerable advantage. EM indicated that as the focus of the value analysis team drifts to other products, it is important that the supplier continues to monitor and report on its success in delivering on the agreed-upon targets - the supplier-HCO relationship is dependent on progress and course corrections as necessary. Because of this, BS indicated that “reverse-value-analysis” may be required, meaning that the overall determination of value is not in the product itself, but evidence supporting that the total value of the supplier’s product-service-monitoring solution truly achieves sustainable outcomes.

If collaborative research can demonstrate long-term benefit for the facility, it will achieve what HCOs are looking for: the ability to set multi-year, long-term agreements with suppliers and their products – minimizing variation and the cost of change.

By any other name, value is just as sweet. The cheap and cheerful offerings of superficial supplier transactions should make one weary of strangers bearing gifts. Instead, we must be advocates for ensuring our decisions access the best possible total value throughout the care continuum. In value analysis, we need to be the guardians of both the care our patients receive and the financial well-being of our own institutions. To achieve all these things, we need the right relationship: a total-value partner willing to work together toward sustainability.

|

James Russell RN-BC, MBA, CVAHP |

|

Eric Mesimer, MBA Vice President of Operations |

|

Ritchey Graham, CWCA Director of Business Development |

|

Barbara Strain, MA CVAHP |

Dr. Tod Brindle, PhD, MSN RN CWCN;

U.S. Medical Director

Allyson Bower-Willner, MBA;

Marketing Director Strategic Accounts

Sarah Tuttle, MS;

Director of Health Economics

Dr. Sara Rook, PhD;

Medical Writer

- Graham G, Cusick C. Facing management’s supply dilemma with healthcare value analysis. Management in Healthcare, 2016; 1(3): 254-260(7).

- Chee TT, Ryan AM, Wasfy J Border WB. Current state of value-based purchasing programs. Circulation, 2017; doi:10.1161/CIRCULATION HA.115.010268

- Russell J. Value analysis and nursing leadership: powerful collaboration in the new financial paradigm. Nursing Management, 2018; 49(9): 40-44. Doi:10.1097/01.NUMA.000542294.52130.a6

- Engleman DT, Boyle EM, Benjamin EM. Addressing the imperative to evolve the hospital new product value analysis process. JTCVS, 2017; 155(2): P682-685.

- Rosenfield J. How patient satisfaction scores are changing medicine. Medical Economics Journal, 2019; 96(21): retrieved from: https://www.medicaleconomics.com/view/how-patient-satisfaction-scores-are-changing-medicine